Housecleaning is perennial ─

universal ─

endless, according to housewives the world over. The ladies in Great Village

have long ago finished the intensive whirlwind called spring cleaning, when

every carpet is hung on the line and beaten fiercely to discharge as much

winter's dust as possible; when every quilt, blanket, sheet and pillow slip is

washed; when every corner of every room, high and low, is scrubbed and swept; when

ever cupboard is cleared of every dish and cup and everything is washed; and

often a fresh coat of paint is applied to sills, frames, doors, even floors,

and new wallpaper is hung on the walls to spruce things up after the

accumulation of smoke from lamps and stoves lit continuously through the long,

cold, dark winter. At spring cleaning time, which stretches from April into

May, houses in Great Village ─ all

along the shore, in Truro, across

the province ─ hum. On lucent

early spring mornings the percussion of the carpet chore sounds like a military

march.

Spring cleaning is a very serious matter, a major

operation. Women prepare for it all winter, just as the farmers prepare for the

spring ploughing and planting ─ they plan their

strategies, repair equipment and lay in supplies. Like the planting, spring

cleaning is a time regarded with resolution (or resignation) and anticipation.

However, unlike the farmers and their planting, women have been housecleaning

all winter, so the resignation is stronger. Still, it is something which must

be done and most of the ladies say, “The sooner the better.”

By this first day of summer the spring cleaning is

well past, though this is often the time when men decide to start the big jobs

of building: a porch, a verandah, an ell. The women think of all the mess that

it will create, workmen tracking in dirt. But all the ladies say that is the

nature of housework, “It is never done.” Death and taxes might be the two

certainties of this world, but ask a woman and she will add, “So are dirty

dishes and laundry.”

Housework has its own conventions and rhythms,

followed more or less by Great

Village ladies. Monday is

wash day ─ a

rainy Monday is a frustrating day indeed. On a clear windy morning the village

clotheslines are adorned with blouses and skirts, shirts and trousers, towels

and tablecloths, bibs and diapers and pinafores ─ the

flapping, slapping clothes are festive and heartening. A good line of laundry,

hung just right (everyone has a theory about which items to hang where) is a

matter of pride for each laundress. Indeed, Great Village

ladies casually or deliberately assess each other’s laundry achievement,

offering critical admiration or disdain, as if it is a work of art. There is a

rivalry among them in the same way as there is a rivalry among the horse owners in the village: friendly

but exacting. This rivalry extends to house cleaning in general. Keeping a

clean house is an aim or a burden for all housewives. The ladies of Great Village

are so often in each other’s homes that they have many opportunities to assess

each other’s successes or failures. Some say too many opportunities.(1)

Laundry is one of the most physically exacting chores.

Kettles of water are heated and poured into large wash tubs. Scrubbing is done

on washboards with large cakes of soap. The hardest part is wringing out the

heavy wet clothes. A few of the village ladies have wringers which attach to

the tubs, a roller machine through which the clothes are fed, which squeezes

out the water. These ladies are the envy of the others.

Monday being wash day, Tuesday and Wednesday tend to

be devoted to ironing. This chore is the most tedious and tiresome, but one of

the most necessary. In the summer, when starched linens are most necessary,

ironing is a wearying task. Flat irons have to be kept hot on the stove, and on

the sticky, close July or August days having the stove fired up, standing for

hours over frills and hems, creases and lapels is monotonous. The stove tends

to be fired up all summer anyway, for cooking and baking. Many village homes

set up summer kitchens, rooms or ells which are more airy than the closed in

winter kitchens. Even so, most women try to do their baking and cooking as

early in the morning as possible during the summer. The end of the work week

(Thursday or Friday) is when the ladies do most of their baking for the week:

bread, rolls, biscuits, pies, squares, cookies, cakes ─ and

cooking the roasts of beef, lamb, veal, pork or chicken. Winter cooks offer

steaming hot soups, stews and casseroles, summer cooks offer cold sliced ham or

chicken salad. Even at the dining table summer meals tend to be picnics, unlike

the more formal feasts of winter's piping bowls. Already, because the late

spring weather has been so pleasant, the young folks have begun picnicking. The

ladies have put out their chaise lounges and little tables on verandahs and

lawns and look forward to the less hectic afternoons when the serious indoors

cleaning is done (before the tea time tasks must be started) and they can sit

down and take up their sewing.

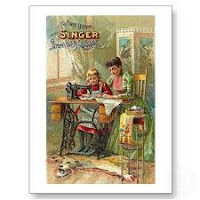

Most women in the village still make most of their

family’s clothes, and sewing is another of those endless tasks. By the first

day of summer the seersucker suits and the cotton frocks have already been made

or mended and spruced up with new buttons or a new lace collar. That work is

done during the winter. At this time of year women are thinking about fall and

winter garments, taking out each flannel and worsted, each vest and chemise,

each coat and cape, and deciding what new is needed, what can be repaired.

Since summer is a time for weddings, not a few women in the village are also

busy putting final touches on trousseaus and bridal gowns.

Of course, not every woman in Great Village

makes her family’s clothes, or makes all of them. There has always been a

tailor and several seamstresses in Great

Village. They are

patronized sufficiently to earn quite a decent living. More and more women are

choosing to order from the Eaton's catalogue or to buy ready made clothes at Layton's, or drive into Truro to the specialty shops. Still, sewing

is one of the most pressing chores women in the village have on their housework

plate. Girls learn to sew as soon as they can hold a needle and thread, and

many ladies in the Village are experts at seams, hems, darts and button holes.

Many have their own Singer sewing machines (they are almost as common as

pianos). The ladies of Great

Village also excel at the

needle arts: crochet, embroidery, needlepoint, knitting, rug hooking and quilting.

One of the favourite gatherings for women is the quilting bee. The Great Village Sewing Club has been

around for years and many a lass received her total immersion in the fine

needle arts amidst the gossiping ladies around the quilting or hooking frame,

or in a circle with the knitting needles clicking. The war has added another

layer of work to this part of daily life. The village ladies are prodigiously

productive in making surgical gowns and knitting socks, mittens ad scarves. The

older and younger ladies tend to do most of this work because wives and mothers

still have to attend to torn overalls and wee ones growing too fast out of

their jumpers. Yet just about every woman in the village contributes at least a

bandage to the Red Cross Knitting and Sewing

Society.

While the farmers are off ploughing and planting the

big fields of grain, most homes in the Village have kitchen gardens. The men

often help with the planting and tending of these vegetable and flower plots,

but the housewife is mostly responsible. Children are often conscripted to do

the endless weeding. Though too early in the season for most crops, already

there has been lettuce, and the fine weather is bringing along the seeds and

seedlings, especially for those who guessed right and got a start of planting.

Some village farmers use cold frames, starting plants as far back as March. And

window sills throughout the village have also been sprouting herbs and

tomatoes, as well as flowers, for months.

The ultimate work of these kitchen gardens starts

later in the season when the pickling, preserving and canning gets underway.

Even this early in the growing season thoughts have turned to these tasks. What

everyone loves of the first strawberries, cherries, raspberries and vegetables

is the freshness. The jars and bottles of preserves in cold cellars have

dwindled and the anticipation of fresh produce is keen for everyone. Yet the

ladies cannot indulge only in providing the first tender beans or peas. They

must prepare for next winter. Canned goods might be more plentiful in the

general store, but most folks still want home-made. And every cook in Great Village

has some specialty which is regarded as the best version. Preserving season is

still some time away though, and for now, fresh fruits and vegetables are on

the menu.

Besides all the cooking, washing and sewing for their

own families, village women also keep busy year round baking and sewing for

society meetings, bake sales, fund-raising dinners, bazaars. Invariably, when

baking or cooking for their own tables there is an event coming up to be

supplied, so an extra pan of squares or a second casserole is made. More often

than not the ladies are meeting in someone’s parlour or having ladies in of an

afternoon to discuss some pending activity (a party, a wedding, a fair, a

concert). Afternoon is the time for calling on neighbours anyway. All these are

reasons to have a tidy house. Every hostess wants to serve at least a ginger

snap with tea.

The celebrations surrounding Dominion Day will be given extra attention this year, as several

organizations will be raising money for the war effort: a bazaar with a pie

sale and fancy tables, an auction and strawberry supper have been organized. So

the ladies have been and will be busy. The missionary lecture this evening will offer tea and a sweet table,

and donations will be accepted in support of the work of the Mission Bands.

It is rare to find Elizabeth Bulmer on a weekday

morning sitting in her rocking chair by the widow. The breakfast dishes are done

and the kitchen swept, though she needs to make a pan of biscuits and tidy up

the everyday parlour, finish straightening up the bedrooms. All the ironing was

done yesterday, a long session of it to get Gertie’s clothes ready. Gertie is

so fond of her nice clothes. They weren’t sure how many dresses Gertie would be

able to keep with her at the hospital, but they got as many ready and packed as

would fit in one of the small steamer trunks. Will and the girls were up early

and off to Londonderry Station.

Mary went off early too, fishing with her friends. It will mean some work upon

her return, to clean the fish. Elizabeth

knows Mary will bring an ample supply for she is almost as good a fisherman as

Art. But it also means that tea is taken care of, nice fresh pan-fried trout, a

lettuce salad (her leaf lettuce is good this year), and the fresh biscuits.

Lunch time will be some egg salad sandwiches, which reminds her that she must

go check the hens. As she rocks in her rocking chair, Elizabeth stares out the window at the busy

street. Everyone coming and going. She’ll sit there, she thinks, until Elizabeth comes back from

Chisholm's pasture and they can do some gardening together. The wee child loves

to dig in the earth, and is so proud of the little patch all her own. Elizabeth doesn’t really

want to go to the lecture

tonight, but Will says they should try to do it. He’s so hopeful that Gertie

will be home soon, but Elizabeth

sees the sorrow in his eyes, behind his gentle smile. Like her, he is worried. Elizabeth doesn’t want to

use the word doubt. Nobody knows, she thinks, picking up her knitting, watching

the road up Scrabble Hill for her granddaughter. God’s will is so difficult to

fathom. It is not up to us to do so, she thinks.

Panoramic view of Great Village

When Will arrives back he stays outside busying

himself with the wagon. Elizabeth

serves the sandwiches on the verandah, a treat her granddaughter delights in ─ like

a picnic. In the afternoon Will goes off to Glenholme with Arthur and Billy and two of the Spencer boys, to

install a furnace. It is hard to convince the child that she must stay home,

hard to say no; but the men will be too busy to tend to her. Elizabeth convinces her granddaughter that it

is better to remain with the promise that she can help clean the fish Mary will

bring home. Elizabeth

marvels at the curiosity of her wee granddaughter, always full of questions,

and she's inherited the family's fascination with fish and fishing. Besides, Elizabeth tells her, she

needs to fetch Nelly, who would be lonely without her company on the walk home

from Chisholm's pasture.

Notes

1. Elizabeth Bishop remembered the keen commitment of

her Aunt Mabel Bulmer’s housekeeping, in a memoir about her Uncle Arthur

Bulmer, “Memories of Uncle Neddy.” In this memoir she called Mabel, “Aunt Hat”:

“Mondays, Aunt Hat energetically scrubbed the family’s clothes, summers, down

below, out back. On good days she occasionally burst quite loudly into song as

she scrubbed and rinsed:

Oh, the moon shines tonight on pretty Red Wing,

The breeze is

sighing,

The night

bird's crying.

Oh, far beneath the sky her warrior's sleeping

While Red Wing’s

weeping

Her heart

awa-a-y...

This song is still associated in my mind not

with a disconsolate Indian maiden and red wings but with a red blouse, red

hair, strong yellow laundry soap, and galvanized scrubbing boards (also sold in

Uncle Neddy’s shop; I forgot them). On other weekdays, Aunt Hat, as I have

said, cleaned house: it was probably the cleanest house in the county. The

kitchen linoleum dazzled; the straw matting in the upstairs bedrooms looked

like new and so did the hooked rugs; the ‘cozy corner’ parlor, with a red

upholstered seat and frilled red pillows standing on their corners, was never

disarranged; ever china ornament on the mantelpiece over the airtight stove was

in the same place and dustless, and Aunt Hat always seemed to have a broom or a

long-handled brush in her hand, ready to take a swipe either at her household

effects or at any child, dog, or cat that came her way. Her temper, like her

features, seemed constantly at a high temperature, but on bad days it rose many

degrees and she ‘took it out,’ as the village said behind her back, in cleaning

house. They also said she was ‘a great hand at housework’ or ‘a demon for

housework’; sometimes, ‘She’s a Tartar, that one!’” (Collected Prose 239-40).

No comments:

Post a Comment