If you are anywhere near Great Village on Saturday, 29 October 2022, get yourself to the Elizabeth Bishop House for an exciting poetry reading, hosted by writer-in-residence Margo Wheaton. A stellar group of poets will reading! After all the damage and challenge presented by Hurricane Fiona, it is great to see the literary arts alive and well in the village.

Friday, October 21, 2022

Wednesday, September 28, 2022

Hurricane Fiona and Great Village

One of the most iconic buildings in Colchester County was damaged by Hurricane Fiona, which roared through the eastern part of Nova Scotia on 23-24 September 2022. The 112-foot steeple of St. James Church, now the Great Village Arts and Entertainment Centre, took a direct hit from wind, which knocked it off its axis. This structure, a registered heritage property, has stood for over 125 years, taking all kinds of weather. So that the winds of Fiona caused this damage indicates just how intense a storm it was.

All who

drive along Highway 2 from Truro to Parrsboro see this building, which stands

at the centre of Great Village. It is the heart of this historic community,

which has been immortalized in the writing of the poet Elizabeth Bishop, who

grew up under its spire.

Below are

some images of the damage and the process to remove the steeple. Just what will

happen is still up in the air (no pun intended). From my perspective, I hope

the will and the resources either to repair and restore it, or to

rebuild/replace it) exists.

Great Village Antiques (directly across the road from the church) has been sharing

images and updates on its Facebook page. As has the Arts Centre, on its Facebook page. Word about this damage has spread far and wide, especially in the

EB world. I have received messages from people as far away as the U.K. and the

U.S.

In today’s

Chronicle Herald, John Demont has written about the damage to the church, and

to other natural iconic structures that did not survive the force of Hurricane

Fiona:

JOHN DeMONT: How disasters teach us to how to master loss | SaltWire

Thursday, August 25, 2022

Viewing Window for John Scott's Elizabeth Bishop and the Art of Losing

The full version of Elizabeth Bishop and the Art of Losing will be available online via Eventive for a short window beginning Friday, August 26th, at 12:00 Canadian/US Eastern time (13:00 Atlantic; 13:30 Newfoundland; 15:00 GMT) until Sunday, August 28th, at 24:00 Canadian/US Eastern time (Monday, 29 August at 01:00 Atlantic; 01:30 Newfoundland; 03:00 GMT) at this link:

Wednesday, June 1, 2022

Elizabeth Bishop Society of Nova Scotia -- Annual General Meeting in Great Village

We are excited to announce that the EBSNS will hold an in-person AGM in Great Village, N.S., on 25 June. We will welcome writer Laura Churchill Duke as our special guest. We also have an exciting announcement about the acquisition of an important Elizabeth Bishop artefact. Everyone is welcome!

Thursday, May 12, 2022

A Riverside Reading of EB Poems as recalled by Emma FitzGerald

To mark the closing of National Poetry Month, LaHave River Books in LaHave, Nova Scotia, hosted an afternoon reading of Elizabeth Bishop poems on Saturday April 30th, 2022.

There were 4 readers: Lisa McCabe, a poet based on the Dublin Shore; Janet Barkhouse (“Jannie B”), a self-described fan of the bookstore, as well as a writer of books from Clearland; Sandra Barry, my host here on the blog, as well as a Bishop scholar based in Middleton, and Black Point’s Carole Glasser Langille, a poet and author of the newly released collection of poems Your Turn.

(The readers, left to right: Janet, Lisa, Sandra, Carole.

Photo by Brenda Barry. Click images to enlarge.)

The setting, as always when at LaHave River Books, was pinch yourself picturesque. The interior of the bookstore, so homey with its wooden bookshelves, chairs, floors and even a piano, with geraniums and cacti at the window, and of course, books upon books.

(Interior of LaHave River Books. Photo by Brenda Barry)

Beyond the windowpanes the LaHave River, more ocean than

river, lay flat and blue grey, and along the shore some small buildings

surrounded by sparse trees were in view.

(River through the windows. Photo by Brenda Barry)

The room was full and after introductions from book shop staff member Marion, the poems were read:

1. First Death in Nova Scotia (read by Lisa McCabe)

2. Filling Station (read by Lisa McCabe)

3. Sestina (read by Janet Barkhouse)

4. Poem (read by Janet Barkhouse)

5. At the Fishhouses (read by Sandra Barry)

6. Sandpiper (read by Sandra Barry)

7. The Moose (read by Carole Glasser Langille)

8. Don't Kill Yourself (a poem translated by Bishop, written by Carlos Drummond de Andrade, read by Carole Glasser Langille)

This was followed by an encore:

9. Shampoo (read by Lisa McCabe)

10. The Bight (read by Janet Barkhouse)

11. Five Flights Up (read by Sandra Barry)

12. One Art (read by Carole Langille)

(Those gathered. Photo by Brenda Barry)

What followed was a lovely chat, a kind of volley back and forth across the room, of warm reminiscences.

First there was a memory of hearing Bishop speak at the Guggenheim in NYC (Carole), which was followed by a memory of reading “Primer Class” for the first time and seeing her own early school days in the Maritimes described, hatching a lifelong thesis (Sandra). Then there was a discussion of that strange indrawn breath described in “The Moose” and finding its echo in Scotland (Carole), adding resonance to Lisa's initial sharing of visiting Bishop's grave in Worcester one cold day in “sloppy snow” and finding a vintage robin's-egg-blue typewriter on the grave, and Janet's declaration that Bishop wrote “The Bight” in Florida on her own birthday. The personal seemed so intertwined with each reader's experience of getting to know Bishop and her work, and you can't help but sense that it is a never-ending journey.

It was a very satisfying time and was followed by the serving of a “Queen Elizabeth Cake,” big enough to feed everyone present. Andra, the owner of the bookstore, ever gracious and cheerful, had made it for the occasion. It provided a nice, sweet snack before we dispersed and made our way back to our respective homes on an appropriately cold spring day.

(The cake, almost gone! Photo by Brenda Barry)

***************

Emma FitzGerald is an illustrator living in Lunenburg, N.S. She illustrated Rita Wilson's A Pocket of Time, about EB's childhood. Her most recent book, with writer Andrea Curtis, is City Streets Are for People.

One of Emma's drawings of the riverside reading was of Sandra Barry.

Wednesday, April 27, 2022

Reading of Elizabeth Bishop poems in Key West

From our Key West correspondent Malcolm Willison: To mark National Poetry Month members of the Elizabeth Bishop Key West Committee held a virtual reading of her poems which was recorded by Valley Shore Community Television. You can access the reading online by clicking here. The reading is about an hour long and features a number of writers, including Malcolm, with strong ties to Key West.

Monday, April 18, 2022

Review of Jonathan Post’s Elizabeth Bishop: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2022) by Angus Cleghorn

This very long series of over 700 volumes may not always be introductory. Such is the case with this fine book by Jonathan F. S. Post, Distinguished Research Professor of English at UCLA. The writing is clear enough for an introductory reader and compounded by expertise that displays knowledge of English poetic history as well as Bishop’s oeuvre. I was happy to bounce around from poem to poem to consider similarities and developments. A first-year college reader might drop a few balls with the mental pinball machine. Still, I would recommend this book to any reader of Bishop because Professor Post’s insights are fine-tuned with a good ear and extensive poetic foundation. The author cites Eleanor Cook; this book has a similar down-to-earth perceptive mastery that one finds in Cook’s books, such as Elizabeth Bishop at Work.

In

order to find references to scholars the reader has to turn to References at

the back of the book as there are no in-text citations or footnotes. I found

this annoying because I had the sense that some of Post’s information was

coming from sources but I could not see any. It makes the pages appear to lack

academic integrity. I suppose the Oxford series is aimed at a general reader

who prefers not to be weighed down by academic references, but Dr. Post’s

academic skills and experience are such that I’d prefer to see where some ideas

come from. I’ve always found footnotes cumbersome, but basic in-text citations

would help. It wasn’t until I was a few chapters in that I finally turned to

page 127 to find References. Nothing in-text leads the reader there.

Upon

first reading page 1 from this Very Short Introduction, I was concerned because the first heading is “The Bishop

phenomenon,” which is a recognizable title of a well-known essay by Thomas

Travisano, and yet there is no citation for it: is this mere coincidence or a

gaffe? It is troubling in a book that’s supposed to have authority. Two pages

later a poem title was incorrectly printed as “Sub-Tropics” when Bishop’s prose

poem series is actually called “Rainy Season; Sub-Tropics.” The first part of

the title is crucial in this “vignette,” as Post describes the three

substantial prose poems on sub-tropical critters. My growing sense of dread was

compounded by repetitious mis-appellations of “Machedo” Soares. Bishop’s

lover’s name was elsewhere spelled correctly as Lota de Macedo Soares. Sloppy

editing in the Oxford University Press machine. Several pages later Dr. Anny

Baumann was described as a “lifelong friend,” however, Bishop only began seeing

her in 1947 at age 36 as the “Timeline” at the back notes.

Post

began to win me over as he described the “perfect pitch” of speech in “The

Moose.” Also, since I had been wondering about the approach taken in this book

series, I was relieved to find this in chapter one’s “Biographical beginnings”:

the focus of this Very Short Introduction is to introduce

new

readers to her verse,

the one truly inexhaustible ‘story’ of

Bishop’s life. From this

perspective, biography is an

important first step

because places and people, heightened by

memory and travel—those

features of inner and outer geography

so crucial to Bishop—are

part of the fabric of her verse. (10)

Nice balance there.

It’s the readings of the poems where Post excels. With Bishop’s late autobiographical poem “In the Waiting Room,” Post describes the retrospective narrator’s experience as a “child’s frightening identification of herself as female” while listening to her aunt cry out in pain in the dentist’s office, leading to Bishop’s self-consciousness amidst humanity: “But I felt: you are an I / you are an Elizabeth, / you are one of them. / Why should you be one, too?” Post plays with numbers adeptly:

Yes, ‘one, too’, a

female, that is, but as ‘one’ becomes ‘two’, the young

girl, having been made

uneasily aware of her body, her gender, and

her connection to

others, separates from the child and, assuming

the adult poet’s

consciousness, comes into the ‘night and slush and

cold’ of Worcester on

the ‘fifth | of February, 1918’. The date

reminds us that ‘The War

was on’, outside as well as inside. (13-14)

Complex and accurate. We

next read about “Sestina,” also from 1976’s Geography

III. I especially like how Post does not try and fill in biographical

particulars beyond what the poem offers. There is a tendency in Bishop

criticism to inject copious details from the life into the art, which Post does

not do, and which is a measure of respect:

We don’t know why the

grandmother is crying, although she hints that her

tears are environmental

and seasonal, and are possibly connected,

moreover, to a larger

world of fate as foretold by the almanac.

Since only the

grandmother talks, we’re also not sure of the exact

bond between adult and

child, the family ties behind an afternoon

teatime ritual, although

the child certainly wishes to please the

grandmother by proudly

showing her a drawing of a house. (16)

It’s important for readers to not say too much and make assumptions about the object of the poem’s grief. Is the man with tear-like buttons Bishop’s father or grandfather? It is a child’s drawing so we can’t pinpoint identity beyond the poetic representation.

Next are “Filling

Station” and “First Death in Nova Scotia.” By the end of this very substantial

chapter 1 it’s evident that this is no breezy Introduction. “Filling Station” is potentially linked, rightly so, to

the gas station across from the Bishop-Bulmer house in Great Village (now

Wilson’s). “Somebody loves us all” finishes the poem with potentially divine

and parental overtones. “To the psychoanalytic critic, she is a compensatory

sign for the mother Bishop lost …” (20). Here we see theoretical framework and,

beyond that, interpretation extends to Bishop’s greatest prose story, “In the

Village,” which begins with “mother’s wrenching scream” (20). Not many

introductory readers will have read “In the Village” but this interpretive

reach is necessary to read Bishop’s poetry in connection with the life in her

One Art. Post returns to the end of “Filling Station” and its “loves”:

Not all of these

contexts are equally persuasive, but one more

suggestion is needed. I

think it is possible to read this gesture

rhetorically, that is,

on its own terms, as an evocation of hope by

someone momentarily

‘filled’ by what she has seen. Bishop’s poems

often end in an open

space, leaving us not so much reaching

irritably after facts as

simply recognizing, as in ‘The Moose’, that

‘Life’s like that’. A

person, the speaker, moved to questioning the

place of things,

including her place in an initially foreign setting

like a messy filling

station, can sometimes arrive at a better, more

generous understanding

and say just this sort of thing.

Casual expressions of

life experience are intrinsic to reading Bishop. Much of the pleasure comes

from being an accidental tourist accompanying her travels. This chapter ends by

touching on “Questions of Travel”:

But surely it would have

been a pity

not to have seen the

trees along this road,

really exaggerated in

their beauty,

not to have seen them

gesturing

like noble pantomimists,

robed in pink.

“Yes, surely. Who wouldn’t want to be part of this fantastic venture?” (24) To many readers the appeal of reading Bishop is adventure – geographic and verbal.

Chapter 2 is on “Formal matters” and here Post really excels. Contemporary readers will appreciate his vast knowledge of the poetic tradition through centuries. “Bishop’s supreme valuation of formal variety as a means to singularity was certainly one of the reasons she was drawn to George Herbert, and perhaps a reason why, rather surprisingly, she never quite embraced Emily Dickinson” (29). It’s important and enjoyable to trace Herbert’s formal inventions as they affect Bishop’s poetic workings. Other influences near and far such as Robert Frost and the Brazilian cordel make their way into Bishop’s variety. Bishop’s collaboration with Marianne Moore is discussed in an excellent reading of “Roosters.” Here again, though, the lack of clear reference is frustrating when Post mentions the poem’s ‘“violence” of tone’ in quotation marks just like that. Not many introductory readers would figure out that this “violence” harkens back to a letter that Bishop wrote about “Roosters” to Moore, or that Thomas Travisano wrote an essay on Bishop’s ‘“violence” of tone’ in Elizabeth Bishop and the Music of Literature (Palgrave 2019). There is no reference at the back of the book for Travisano’s essay, Bishop’s letter, or anything to explain the odd punctuation here. Sloppy editing.

This

is not Post’s fault. He excels as formal reader of all kinds of Bishop poems,

such as “Questions of Travel,” in which he brings in the Baroque and Hopkins to

pinpoint prosodic iambs, dactyls, extra syllables, spondees, and Anglo-Saxon

beat in this poem that to me sounds like water falling. “Here is not

description per se, but the act of experiencing in the mind what the eye sees.”

This goes back to a reference that is acknowledged in the text to an essay from

1929 by Morris Croll, “The Baroque Style in Prose.” George Lensing has written

beautifully about this in a 1995 special issue of The Wallace Stevens Journal focused on Bishop and Stevens. Croll

and Stevens depict “a mind thinking,” which is part of this section’s heading.

To

some degree Wallace Stevens set the table for his modernist

contemporaries

when he wrote in ‘Of Modern Poetry’, ‘The poem

of

the mind in the act of finding | What will suffice. It has not

always

had | To find: the scene was set; it repeated what | Was in

the

script’ (my italics). There is a great deal of Stevens in Bishop;

Harmonium

was a

book she said she had almost by heart; she

elsewhere

spoke of admiring the ‘display of ideas at work’ in his

poetry.

And there are lines in her poetry that, without the example

of

Stevens, seem unthinkable in their majestic play with

perception:

‘This celestial seascape, with white herons got up as

angels,

| flying as high as they want and as far as they want

sidewise

| in tiers and tiers of immaculate reflections’ (‘Seascape’).

But

‘if accuracy of observation is equivalent to accuracy of

thinking’,

as Stevens himself observed in Adagia, it is Bishop, not

Stevens,

who best fulfilled the modernist ideal of poetry as the act

of

finding on a human scale in a world of familiar and not so

familiar

objects. (42)

Bishop

often found the unfamiliar through animals; this otherness helped her sometimes

criticize human morality, something she found in Marianne Moore’s poetry

…

without condescension, ‘without “pastoralizing” them as [the critic]

William

Empson might say, or drawing false analogies’. And in this

‘unromantic,

life-like, somehow democratic, presentation of animals’

Moore

helped Bishop (who was also aided by her reading of Darwin) to

write

about animals and, more broadly, nature from a sympathetic but

not

exclusively human-centred perspective …. (51-52)

This enables Bishop’s poetry to be read now as a critique of the Anthropocene age. Sometimes Bishop’s animal poems are more closely linked to humanity, as in “The Armadillo” dedicated to Robert Lowell. Chapter 3 focuses on Lowell and Moore as influential practitioners for Bishop’s animal descriptions.

One

of Bishop’s most critical poetic representations of humanity occurs in “Brazil,

January 1, 1502,” which Post discusses with subtlety: “her delving—to redeploy

an idiom from ‘The Map’—into the shadows that inhabit the shallows” (55). Those

shadows become the forest canopy under which indigenous women retreat while

being attacked by rapacious Portuguese colonizers. Post weaves Ovid’s Philomel

story from Metamorphoses as well as

Shakespeare’s The Rape of Lucrece

into the poem’s tapestry to show that Bishop is

appropriating

one kind of violence (sexual) through another (artistic),

to

reveal a world long familiar to the reader but now seen mysteriously

anew,

as only the closely woven fabric of her marvellous art can do.

For

Bishop the explorer, coming to terms with the cheerful natural landscape

means

coming to understand the sometimes awful footprint of

human

history. (59)

Chapter 4 on poetry and painting includes some of Bishop’s paintings from Exchanging Hats by William Benton and continues fine analysis: “We might regard ‘The Fish’ as a painter’s paradise, and also a reader’s” (67). I feel the same way about “Seascape” and “Pleasure Seas.” Excellent examples from “A Cold Spring,” “Santarem,” and “Over 2,000 Illustrations and a Complete Concordance” are canvased. Post precisely notes that only “Large Bad Picture” and “Poem” are technically ‘ekphrastic,’ meaning “a poem about an artwork, usually a painting. The doors open wider if we use ‘ekphrasis’ in the original classical sense of any verbal description of something seen (think ‘Cape Breton’) …” (75). As with many of Bishop’s readers, Post reads “Poem” with delight, as did Howard Moss when he received it at The New Yorker: “I wish I could read a poem like that every day for the rest of my life” (80).

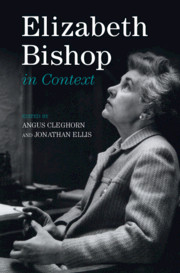

This

book features six illustrations, two of which are photographs by Rollie McKenna

somewhat similar to the cover of Elizabeth

Bishop in Context, which Post wrote to me that he regretted not having read

by the time his book went to press. Chapter 5 on “Love known” begins by finding

Thomas Travisano’s 2019 biography Love

Unknown an unclear title aside from the allusion to the Herbert poem. For

Bishop knew love, as the posthumous poems “It is marvelous to wake up

together,” “Breakfast Song” and “Vague

Poem (vaguely love poem)” display in different ways. Post does nice work

with more subtle expressions of desire such as “Quai d’Orleans” and “Four

Poems,” the latter of which he reads as an experimental poem. A section

entitled “Still explosions” examines “The Shampoo,” and finds its first stanza

perplexing: “Odd to think of lichens exploding” (93). Really? On daily walks I observe

lichens on rocks and their various amoebic shapes do burst (perhaps my eyes

perceive via Bishop’s painterly descriptions). I can forgive Dr. Post’s

different aperture when I read this rich conclusion about the final stanza:

…

set off with a dash (for spontaneity) and a comma (for a pause),

the

single word ‘Come’, a directive that carries lightly the weight

of

an entire tradition of carpe diem poems in English. (Think

Marlowe’s

‘Come live with me’ or Ben Jonson’s ‘Come my Celia,

let

us prove | The sports of love.’) And in that directive, we might

fancy

Bishop taking control of those loose black hairs in ‘O Breath’

that

were flying around, intolerably blown about, and weaving

them

into a love-knot about something as domestically simple and

sensual

as washing a companion’s hair. (94)

While it may not quite be an entire tradition’s weight, we might also find Emily Dickinson’s dash and comma style here. Earlier in the book Dickinson was understandably downplayed in favour of Herbert, but her signature pauses may figure in “—Come,” and in the delayed foreplay of “Four Poems” and its spaces. After “The Shampoo,” Post finds that another domestic poem about Bishop’s love for Lota de Macedo Soares. “Song for the Rainy Season” “… continues the association of eros and aqua, both life-giving forces in Brazil” (97).

“Bishop is the great travel poet of our modern era,” chapter 6 begins authoritatively (103). “[L]yric time and leisurely thinking” are observed by Bishop in a 1965 letter to Robert Lowell referring to “Walking Early Sunday Morning.” At the back of the book we can find reference to Roger Gilbert’s influential Walks in the World: Representation and Experience in Modern American Poetry from 1991. Post locates “‘The End of March’ [a]s a ‘walk poem’ along the shore south of Boston …” (104). Complexity overflows from this poem, especially its accumulative ending. As often the case, Wallace Stevens is read into this poem’s mechanics. To me, the whole poem can be read as a dialogue with Stevens’ metrical form and his imagination embodied in lion figures; Post chooses the “lion of the spirit” from “An Ordinary Evening in New Haven.” Back in 1991’s Questions of Mastery, Bonnie Costello discussed Bishop’s use of Stevens’ lion sun while referring to Harold Bloom’s prior interpretations. The richness of “The End of March” and Bishop’s meta-dialogue with Stevens endures — partly because Bishop’s poem is so playful with its “artichoke” crypto-dream house and flaming “grog a l’americaine” Stevens would enjoy, also because readers can choose a suitable measure of rich textural engagement within the basic message of the poem: “Go for a walk, especially along a beach. It might change your mood, your inner weather, for the better” (116).

From

the influential author of “Sunday Morning” to “Bishop’s ultimate Sunday poem,”

(117) we go to Santarem where the poet’s mind is in motion again; amidst the

“dazzling dialectic” of converging blue and brown rivers, an older Bishop plays

with self-correction, as pinpointed in Post’s knowledge of rhetorical figures:

the

device of ‘metanoi’, meaning ‘afterthought’, for the first time

she

confuses church and cathedral, then again as ‘epanorthosis’

or

‘emphatic correction’, by enjambing the phrase across a stanza

break

and adding an exclamation point: ‘the church | (Cathedral,

rather!)’.

(117)

And yet everything is so well remembered about this place “in which contemplation wins out over commerce” (119). This subtle use of Bishop’s “Large Bad Picture,” and its dialectical “commerce or contemplation” is doubtfully picked up by many introductory readers, and so it remains an unacknowledged reference.

Jonathan

Post in his epilogue does refer to “the classroom. For a number of years, I

taught Bishop in a seminar called, simply, ‘How to Read a Poem’” (120). It is

this pleasure that jumps off the page. One feels the company of a master who

makes it easy, in his own words,

…

because Bishop is so good at taking you through the steps.

First

step, look closely; second step, look closer still; third step

look

even more closely, but especially now with an eye to where

the

poem is going, not to where you think it should be going,

but

where its diction, syntax, grammar, and punctuation

lead.

This means listening to the poem, bringing the ear out of

hiding

in order to help the eye to see and the mind to think.

Bishop’s

poems are always about surfaces getting deeper, about

knowledge

as process. (121)

She “makes us feel that we’re all there as part of the poem’s creative energy at the moment of its arriving” (123).

********************

Angus

Cleghorn teaches English at Seneca College in Toronto, and once explored the

Moose route in Nova Scotia during a stay at the Bishop-Bulmer house in Great

Village.

Thursday, April 7, 2022

Reading of Elizabeth Bishop Poems to Mark National Poetry Month

I am honoured to be participating in a reading of Elizabeth Bishop poems at the LaHave River Bookstore on Nova Scotia’s South Shore on 30 April 2022 at 4:00 p.m. I will be joined by three other writers: Janet Barkhouse, Carole Langille and Lisa McCabe. You can learn more about the wonderful LaHave River Bookstore by checking out their website and Facebook page. Hope to see you there.

Monday, March 21, 2022

Review: “Elizabeth Bishop in Context: Glimpsing (and Holding) the Poet’s Messy Universe” by Tristan Beach

Introduction

How far back do you go to find the sources of a writer’s life and work? To ancestry and community? To family and childhood? To education and experience? … Art is, probably, created somewhere in the messy middle… it was so for Elizabeth Bishop, who described life as an ‘untidy activity’ (Sandra Barry, “Chapter 1: Nova Scotia” 17)

Elizabeth Bishop in Context, edited by Angus Cleghorn and Jonathan Ellis, is a groundbreaking, comprehensive collection of essays that penetrates and reveals numerous facets of Elizabeth Bishop’s life and legacy—observed within and across different contexts. Cleghorn and Ellis write in their introduction, “Contexts do not provide all of the answers to the many questions her poems and stories ask. In some cases, it feels as if they make things messier… What happens when one context contradicts the other? Which context matters more? Why these contexts and not others?” (2). Cleghorn and Ellis do not attempt to answer these questions; rather, they let the collection speak for itself. And, as Sandra Barry notes in her chapter on Nova Scotia quoted above, like “Art,” this collection takes its readers “somewhere in the messy middle,” offering numerous overlapping, contrary, and highly unique ways of seeing, and reading into, the person, poet, philosopher, critic, artist, correspondent, and teacher that was Elizabeth Bishop (17).

Structuring the Collective

The thirty-five essays comprising the volume were penned by a global collective of scholars, translators, poets, critics, editors, and admirers. Each essay bears a chapter title corresponding with its respective context, and each context is grouped with other similar contexts under a related thematic section. For instance, Part II. “Forms,” contains chapters on literary, visual, and epistolary genres as contexts such as “Lyric Poetry” by Gillian White and “Translation” by Mariana Machová. Likewise, Part V. “Identity,” includes the contexts of social constructs, such as “Gender” by Deryn Rees-Jones and Eira Murphy, as well as the rich realm of symbols and the unconscious, such as “Dreams” by Bonnie Costello.

These

chapters provide nuanced ways of seeing Bishop’s life and legacy: glimpses into

the mess that the editors and contributors each contend with. The chapters echo

one another in their interpretations either by proximity (in their sequential

chapter order) or by examining common primary sources, such as Bishop’s poems

and letters—or by drawing on frequently cited criticism and biography. Through

these common dimensions each contributor offers numerous similar contextualized

frames for glimpsing Bishop. However, while these chapters briefly (few

span beyond 12 pages long) resemble one another, many through their

dissimilarity appear to enforce the messiness. Thus, collectively the contextualized

glimpses of each chapter do not total, nor do they form, a singular image

of the poet.

Where one chapter may trace the “apocalyptic threat” of WWII in “At the Fishhouses” (Charles Berger’s “War,” which finds in the poem’s “total immersion” a “dream-vision of the world sliding into extinction” 217), another chapter may note the same poem’s musicality and earthly humor (Christopher Spaide’s “Music,” in which the poem’s “total immersion” is identified as being “lifted” from “interdenominational debates over baptism” 239). Coincidentally, both chapters, despite operating from distinct contexts and even more distant interpretations of the same poetry, appear in the same section, Part IV. “Politics, Society and Culture.” Such separate, yet adjacent, thematically related readings of the same poetry, letters, prose, and other primary sources results in complex, nuanced visions of Bishop’s world—more accurately, her universe—that trend more towards complementing than contradicting.

Among the many contextualized glimpses in the collection are Bishop’s childhood detailed in Nova Scotia (Barry’s “Nova Scotia”), as well as her boisterous, troubled years in Brazil—the literary legacy there being politically mired (Neil Besner’s “Brazil,” Machová’s “Translation,” Maria Lúcia Milléo Martins’s “Brazilian Literature”). Other glimpses can be found in Part III.’s “Literary Contexts,” which includes romanticism, surrealism, modernism, among others. These chapters detail Bishop’s encounters with the different movements, locating through hints or outright declarations in her letters and poems her resistance, dismissal, or embrace of such movements. Also of note is her ambivalence toward psychoanalysis due to several instances of failed psychotherapy as a child but followed by her captivating and complicated friendship with her psychoanalyst, Dr. Ruth Foster (Lorrie Goldensohn’s “Psychoanalysis”). Such ambivalence, typical of Bishop who knowingly held opposites, can be seen in her apolitical public stances yet personal anti-fascist sentiment captured in Berger’s “War,” Steven Gould Axelrod’s “The Cold War,” and Jeffrey Gray’s “Travel.”

These multiple contextualized glimpses into the mess of Bishop’s universe present us with a person whose global influence extends beyond categorization, taking root in our imagination, as Stephanie Burt examines in “Bishop’s Influence,” in Part VI. “Reception and Criticism.” Burt charts Bishop’s far-flung influence—in poetic form, device, attention, subject, and obsession—on American poetry in the 21st century. Just as Bishop’s influence is extensive and her apparent literary descendants numerous, her figure, too, appears multiple, as a collective: we glimpse through Elizabeth Bishop in Context the individual Bishops, the many faces of Bishop that populates this universe. Bishop the social critic, Bishop the alcoholic, Bishop the loyal friend, Bishop the survivor of abuse, Bishop the patient, Bishop the lover.

One common facet among many glimpsed across contexts is Bishop’s queerness, which informed much of her attitudes, relationships, and resistance to literary categorization or being lumped into a single movement (she famously resisted being defined as a “woman poet” and disdained much being anthologized as such). As Axelrod notes in “The Cold War,” Bishop’s position as a queer woman cast her as an outsider to American society, vulnerable to McCarthyism through its rampant, homophobic persecution of sexual and gender minorities. Axelrod locates Bishop’s “binary thinking in the service of queer non-conformity” in her poem “View of the Capitol from the Library of Congress” that castigates white, straight, heteropatriarchal nationalism that dominated the American political experience (223). Axelrod finds that although Bishop “had a ‘horror of Communism’,” her “skepticism toward democracy… reflects queer alienation at mid-century as well as forecasting later strains of liberal unease” (223, 224).

Where Bishop’s queerness underlay her political affiliations and attitudes, it also unpinned her complex relationships with other women and her conception of gender. From childhood to late adulthood, her life was enriched by a global network of female relations—aunts, teachers, mentors, students, friends, and partners. In Rees-Jones and Murphy’s “Gender,” the authors chart the impact of these relations on Bishop as a queer poet. They observe that, inspired by her own intimate relationships and with other women while navigating openly homophobic American society, Bishop’s view of gender was highly nuanced and less monolithic or stable. For instance, the authors describe North & South as “a book of sleepy disorientations; … a book which creates a world in which bodies are not fully assembling or coming together” (315). Here, Bishop resists fully, or at least consistently, gendering her speakers and, at times, their subjects—frequently encompassed in an gender neutral “we” (315).

Yet Bishop’s playful, queer explorations, reversals, and deflections of gender roles and norms are further complicated by her whiteness, which Rees-Jones and Murphy identify in poems such as “In the Waiting Room,” in which Bishop, “[setting] herself in a place of difference from the Black women in the National Geographic,” reproduces “hierarchies… in terms of race [that] risk constructing a racist narrative of difference, a narrative which continues in Bishop’s work” (320). Bishop’s politics, queerness, female relations, gender conceptions, and whiteness—however clearly glimpsed or carefully explained—nevertheless add many depths to the mess of her universe.

As individual readers of Elizabeth Bishop, we may investigate and grapple with the many faces and forms of Bishop. In solitude and with only the original work in our hands, our glimpses of the poet is ever elliptic, partial, and often outside a community of other ways of seeing. However, Elizabeth Bishop in Context attempts to corral the mess without containing or parsing it, despite the collection’s careful organization that resists a single, dominant gaze. By admitting multiple ways of envisioning Bishop and within a collection that covers an exhaustive (though not complete) amount of ground, we as solitary readers gain this community of thoughtful, incisive glimpses grounded in their respective contexts.

Elizabeth Bishop in Context adds a necessary volume to the steadily growing field of Bishop studies, a field whose community history Thomas Travisano narrates in his titular chapter, “Bishop Studies.” Like other recent volumes, including Bethany Hicok’s Elizabeth Bishop and the Literary Archive and Cleghorn’s own Elizabeth Bishop and the Music of Literature, Elizabeth Bishop in Context further elevates and legitimizes not just Bishop studies writ large but Bishop herself as a literary force worthy of study within and throughout multiple contexts. And as Travisano states in this community of scholars, students, readers, and teachers, “it was precisely by learning to read Bishop’s work in context that Bishop studies emerged as the steadily expanding and influential international field that we know today” (author’s emphasis 382).

Tristan Beach is a PhD student in Rhetoric and Composition at the University of Nevada, Reno. He received his MFA in Poetry from Goddard College and a BA in English from Saint Martin’s University. He is a member of the board of directors for Olympia Poetry Network and is the poetry editor for Pif Magazine. His creative and critical writings have appeared in Pif, Conium Review, Shantih, The Pitkin Review, and elsewhere